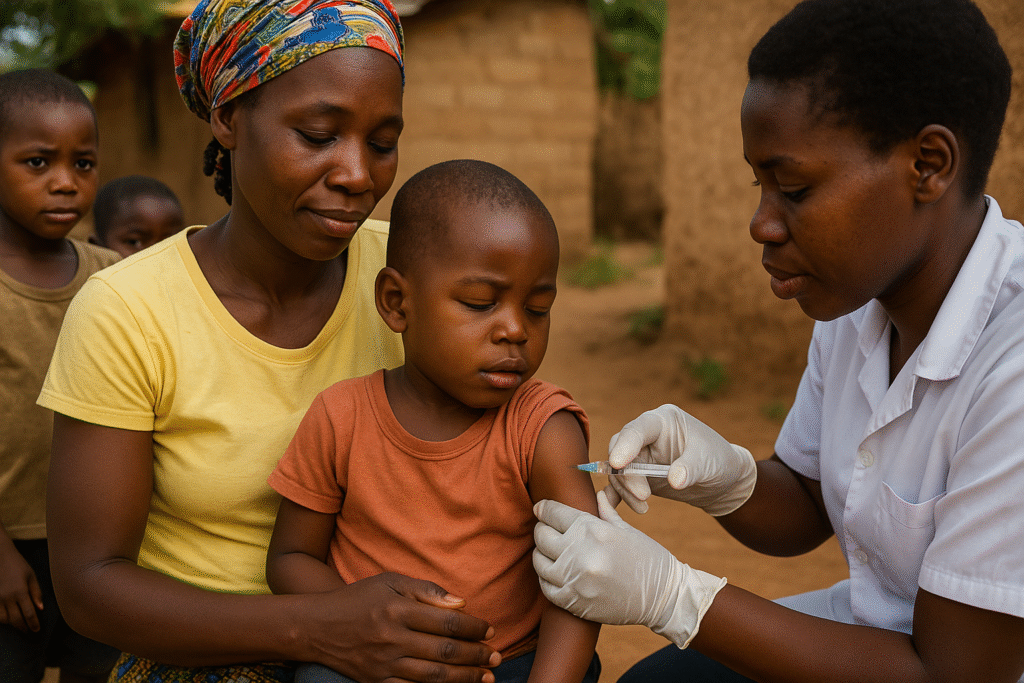

For the first time in history, malaria vaccines are being rolled out on a large scale across Africa. This marks a major step in the fight against one of the world’s deadliest diseases.

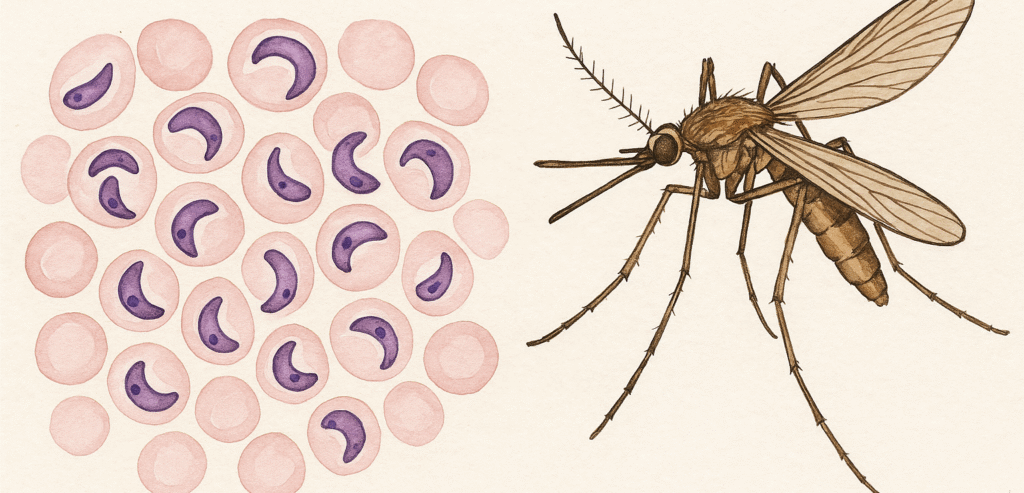

Malaria is a serious disease caused by parasites (tiny organisms) that are spread to people through the bite of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. It kills nearly 500,000 people every year – most of them children under five. Now, with the support of the World Health Organisation (WHO), UNICEF, and Gavi (the global vaccine alliance), countries are adding malaria vaccines to routine childhood immunisations.

Why Didn’t We Have a Malaria Vaccine Before?

Unlike other diseases such as measles or polio, malaria has always been much harder to develop a vaccine for. Here’s why:

1. A Very Complicated Parasite

Malaria is caused by a parasite (not a virus or bacteria). This parasite has a complex life cycle: it changes forms as it moves between mosquitoes and humans. Each stage looks different to the immune system, making it very tricky to target with just one vaccine.

2. Immune Evasion

The malaria parasite is clever—it can hide inside human liver and blood cells. This makes it harder for the body’s immune system to recognize and destroy it.

3. Technology Limitations in the Past

Earlier vaccine technology wasn’t advanced enough to deal with malaria’s complexity. Scientists tried for decades, but results were either weak or didn’t last long enough to protect children.

Recent Malaria Vaccine Breakthroughs

After more than 30 years of research, two vaccines (RTS,S Mosquirix and R21) were finally proven safe and effective. In 2021, WHO recommended RTS,S for use in children. By 2023–2024, production scaled up, and the historic rollout began in African countries.

How Do the New Malaria Vaccines Work?

The two malaria vaccines approved by the World Health Organisation (WHO) are the RTS,S (Mosquirix) and R21. Both are designed to train the body’s immune system to recognise and fight the malaria parasite before it can cause someone serious illness.

- Targeting the Parasite Early: Both vaccines focus on the first stage of the malaria parasite, right after a mosquito bite. When a mosquito carrying malaria bites, it injects parasites into the bloodstream. The vaccines prepare the body’s immune system to recognize this early stage and attack quickly, stopping the parasite from multiplying.

- Four Doses for Strong Protection: Children need a series of four doses (starting around 6 months of age) to build strong and lasting protection. In some places, extra seasonal doses are given before the rainy season, when malaria cases usually rise.

- How Effective Are They? Studies show they can reduce malaria cases by about 50–75% in young children. When combined with other tools—like mosquito nets and medicines—the effect is even greater, reducing severe cases and deaths dramatically.

Historic Beginnings: When and Where It’s Spread So Far

Cameroon was the first country to begin routine malaria vaccinations, starting in January 2024. The campaign aimed to vaccinate around 250,000 children. While the vaccine (Mosquirix) offered limited protection, it marked a historic breakthrough in malaria prevention.

As of early April 2025, 19 African countries—including Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, Chad, DRC, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Sudan, and Uganda—had started offering malaria vaccines as part of routine childhood immunization programs.

Early Results: Are Malaria Cases Going Down?

- In Kenya, more than 100,000 children had been vaccinated by January 31, 2025, in one county. The results? A remarkable drop in malaria among residents—from 27% to 3.6%—translated into over 32,000 fewer severe cases needing hospitalization.

- In pilot programs across Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi, areas where the vaccine was introduced saw a roughly 13% reduction in child deaths, on top of existing malaria prevention efforts.

- When combined with other malaria control tools like insecticide-treated bed nets and seasonal chemoprevention, clinical cases can drop by more than 90% in high-transmission regions.

Why Malaria Vaccine is Important to Public Health?

In the past, malaria prevention strategies focused mainly on controlling the mosquito vector—using insect repellents, insecticide-treated bed nets, and indoor residual spraying. While these methods saved millions of lives, they were often limited by challenges such as insecticide resistance and difficulties in maintaining consistent coverage.

Today, with the development of malaria vaccines, we can also shift our focus toward strengthening host immunity. When combined with traditional tools, this new approach represents a breakthrough in global malaria control, providing both external protection (mosquito control) and internal protection (immune defense). This represents a significant step forward in improving the overall health and well-being of populations worldwide:

- Protecting children: Infants and toddlers are most at risk. Vaccination helps prevent severe malaria and saves lives.

- Proven results: Studies show the vaccines (RTS,S Mosquirix and R21) can cut malaria cases by more than half in young children.

- Life-saving impact: In pilot programs in Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi, child deaths dropped by about 13% in areas where vaccines were given.

- Historic scale: By 2025, more than 20 African countries will roll out malaria vaccines nationwide. For example, Uganda has already given over 2 million doses to children.

The malaria vaccine rollout marks a historic moment in global health. For the first time, we have a tool that can protect millions of children from one of the deadliest diseases in history. While challenges remain—such as funding, logistics, and ensuring full access—the results so far show great promise.

This progress is not just about Africa—it is about all of us. The fight against malaria shows what the world can achieve when science, governments, and communities work together for a healthier future.

Source

- World Health Organization. (2023). Malaria vaccine implementation in Africa. Retrieved from WHO

- Gavi Media Room. Cameroon started early programs; pilot countries saw 13% fewer child deaths. Gavi

- UNICEF/GSK/WHO allocations. Pilot program results in Ghana, Kenya, Malawi. UNICEF

- BBC News. (2025). Africa begins historic malaria vaccine rollout. Retrieved from BBC

- Nature (Aug 15, 2025). Zambia’s national rollout planned Q3 2025. Nature

You may also be interested in Global mental health crisis: Why it is on the rise?

Thank you for this informative article about the malaria vaccine rollout in Africa. It’s encouraging to see the progress being made in protecting children from this deadly disease. I’m planning a trip to East Africa next year and was wondering if these vaccines (RTS,S and R21) are available for adult travelers yet, or if we still need to rely solely on traditional preventive measures? I found some helpful information about malaria prevention for travelers at https://pillintrip.com/ru/article/malaria-prevention-treatment-guide-for-travelers, but I’m not sure if the information about vaccines there is up to date. Apologies for sharing the link, I just thought it might help clarify what preventive options are currently available for travelers visiting malaria-endemic regions.

Hi, thank you for your comment! At present, the malaria vaccines (RTS,S and R21) are not available for travelers. They are currently being used for children in Africa as part of national immunization programs. For now, traditional prevention methods such as antimalarial medication, insect repellent, and mosquito bite protection remain the main ways to prevent malaria while traveling.